Text: Laura Roling

Most opera characters are not blessed with an easy life. So, what does a psychiatrist see when he attends an opera? A dizzying array of mental illnesses and disorders? Or is there more? We decided to ask Flemish psychiatrist and fervent opera lover Dirk de Wachter.

As a regular opera-goer, what would you say is the most common psychiatric disorder in opera?

“A diagnosis is not foremost in my mind when attending an opera – but it isn’t when I’m working with a patient either. That may sound odd coming from a psychiatrist but I want to see my patients as normal people. I have sometimes had a patient sit across from me and when I have asked how I can help, they have replied: ‘I have borderline.’ I don’t find this type of information particularly enlightening. In fact, I believe these types of diagnoses contribute to a patient’s perception of themselves as abnormal. This is at odds with how I want to interact with my clients: I want normality to be the starting point of any conversation. Everyone has something they are good at, everyone has someone they care about and everyone has something they enjoy doing. I think it is important to look at what connects someone to the world, rather than what isolates them.”

Your book Borderline Times posits that it is society as whole that is suffering from borderline.

“Yes, in my book I used the BPD diagnostic criteria to screen our society for borderline. And it turns out our score was pretty high. Our society exhibits many of the classic symptoms of borderline. I was mainly trying to make a point by relying on diagnostic criteria: we have a propensity to medicalise and pathologise things that are inherent to being human. Disease does not just provide insight into a patient, it sheds light on our society as a whole.”

‘I believe these types of diagnoses contribute to a patient’s perception of themselves as abnormal. This is at odds with how I want to interact with my clients: I want normality to be the starting point of any conversation.’

Does opera offer a reflection of who we are?

“Absolutely. Opera characters may sometimes be somewhat over-the-top, but above all, they reflect our human nature with all its weaknesses and flaws. The arts have an uncanny ability to uncover and expose our dark side. Opera has the power to break through our façade of ‘keeping up appearances’ and uncovers what has been hidden away for the sake of social convention.”

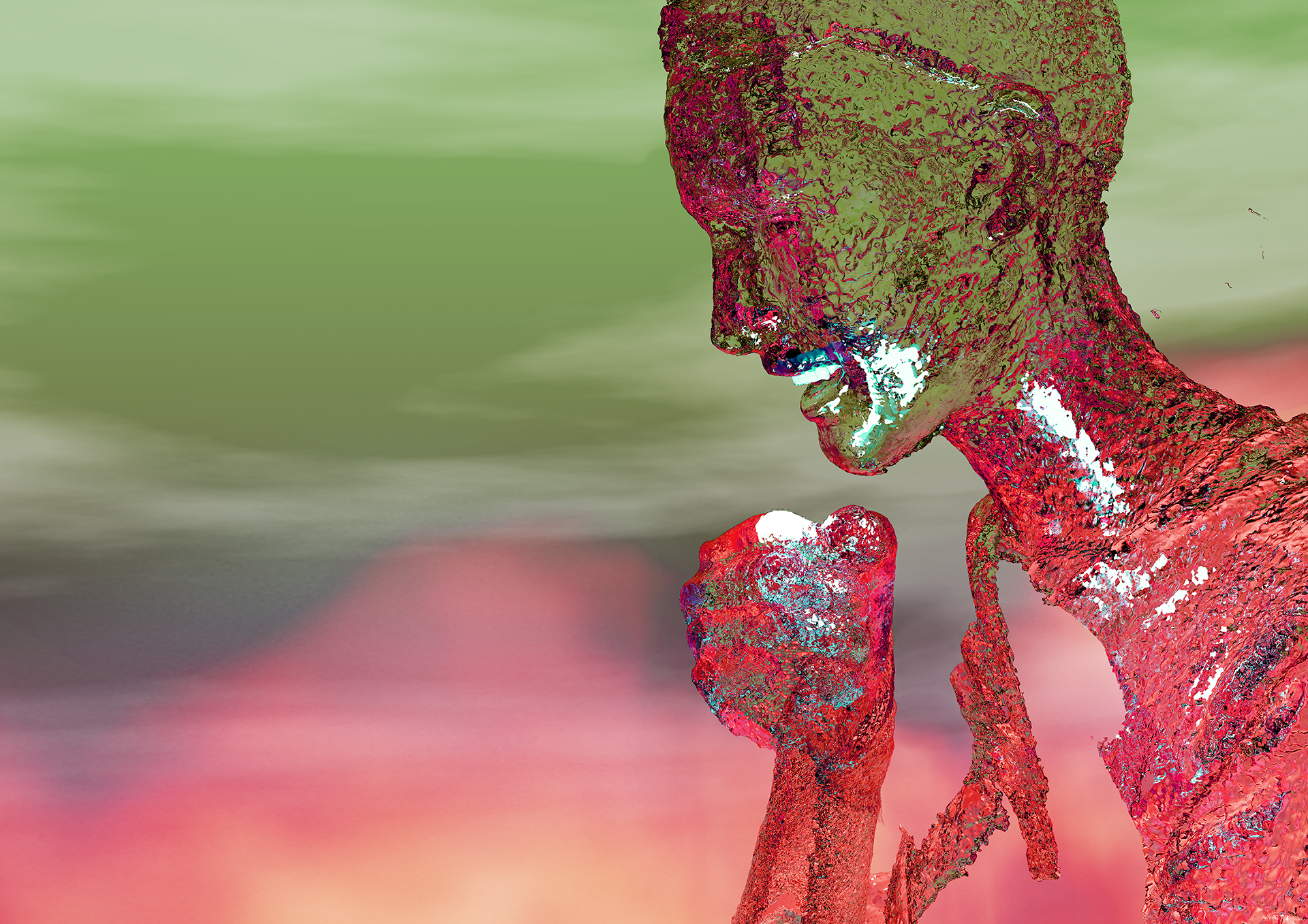

Would you say opera penetrates the depths of our being?

“The arts in general definitely have that potential. I do not believe they are the icing on the cake, rather they are the base – fundamental to everything. Art was born when mankind first became aware of the incomprehensibility and inevitability of death. The powerless our ancestors felt in the face of death unleashed a wave of creativity, causing them to dance, chisel stone, tell stories and sing. All of the art forms are, in one way or another, connected to life and death.”

Would you say this is especially true of Orpheus and Eurydice – the legend that has inspired two of the operas in the Opera Forward Festival?

“Absolutely. It might be an ancient legend, but it is still incredibly relevant. While times and circumstances may have changed since this myth was first created, the essence of mankind has changed very little. The stark boundaries that separate life and death, the fact that we control very little in our lives and the fact that we cannot return from the dead - these are issues that all of us face in our current lives.”

What does opera mean to you?

“Well, I have a première subscription package to the opera in Antwerp, and I always try to go to an opera whenever I’m in another city for a conference or lecture. This means I have seen many operas in different cities across the world. I would also say my taste in music is quite eclectic. I’m very fond of the opera classics, but I’m also interested in new and innovative compositions. For instance, one of the most memorable and extraordinary operas I have ever seen was Schoenberg’s Moses und Aaron in Berlin.”

‘The stark boundaries that separate life and death, the fact that we control very little in our lives and the fact that we cannot return from the dead - these are issues that all of us face in our current lives.’

Do you feel your patients could benefit from going to the opera?

“I definitely believe in the power of the arts and that opera can help us confront our dark sides. But that doesn’t mean I’ll tell a patient mid-session: ‘Why don’t you try going to the opera? I think it might help you.’ I follow my patient’s lead in terms of their interests and passions – it is not my place to impose my worldview on them. My job is to listen, not to preach.”

And what if your patients enjoy going to the opera?

“Then it is up to me to ensure we don’t veer off track by getting caught up in conversations about art. Sessions with my patients need to focus on the prosaic banalities of everyday life, as this is where they experience distress and run into difficulties. It is important not to avoid talking about these issues. I once treated someone from the opera world and had to exercise considerable self-restraint in this regard – the person in question was primarily struggling with problematic relationships, not with their artistry. The arts do, however, take centre stage in creative therapy.”

How important is this kind of treatment?

“Creative therapy can certainly by a highly effective tool for people who have difficulty expressing themselves. Art or music provides patients with an outlet, through which they can articulate their suffering. The aim is not to create high art or anything, but to harness creativity as a means of expression. It offers patients an alternative form of communication, allowing them to go where words cannot.”

‘I want opera to move me in a way that transcends rational understanding and analysis. I want to be blown away.’

Would you say this is what makes the arts and opera so special?

“Absolutely. I want opera to move me in a way that transcends rational understanding and analysis. I want to be blown away. Opera touches people, using alternative forms of expression. This is what opera is all about – being able to understand an opera rationally is only of secondary importance.”

Would you advise novice opera-goers keep this in mind when attending an opera?

“Yes, definitely. I would say go to the opera with an open mind and allow yourself to be swept away. Let the emotion and drama penetrate the depths of your being. Don’t be afraid to face the darkness. We often place a great deal of value on things being ‘fun’ or ‘enjoyable’. But things don’t always have to be fun or enjoyable. In fact, often they aren’t. There is no need for opera to shy away from this fundamental truth.”